Freedom of Form | Carel Visser, the later years

The Collectie Nederland boasts two iconic paintings by two of the world's most renowned modern artists: Henri Matisse's colossal 1952 masterpiece The Parakeet and the Mermaid, which occupies an entire wall in the Stedelijk Museum, and Piet Mondrian's 1944 Victory Boogie-Woogie, in the Kunstmuseum Den Haag. Both are jewels in the canon of modern art. The similarities between these two masterpieces are striking. Both consist of a combination of gouache (Matisse) or oil paint (Mondrian) with the use of collage. Matisse pasted his bright-hued 'papiers coupés' onto large panels, while Mondrian experimented with vivid 'paper tapes' on painted canvas. But that is not the only thing they have in common: both paintings are among the last works produced by both Matisse and Mondrian. In 1952, Matisse was already in his 80s, while Mondrian was still working on his Victory Boogie-Woogie at the time of his death in New York in 1944, aged 72.

A remarkable number of artists across the disciplines produce outstanding work late in life, sometimes even reaching the apogee of their artistic achievement. In the music industry, it is by no means unusual for composers, soloists and conductors to still be performing at the top of their game well past retirement age. For all that youthful 'Sturm und Drang' can be a cauldron of truly great art, there is a certain freedom of expression that comes with age. Drawing on years of knowledge and experience, the older artist eschews style conventions and expectations, and is free to focus uniquely on his or her personal conception of art.

Carel Visser is one such artist who, in the later stages of his illustrious career, realised he was free to do as he pleased. Visser's oeuvre spans an entire lifetime. The early years were typified by studies in a somewhat figurative visual language; the 50s and 60s were full of abstract geometric iron shapes, stacks of beams, studies of tilt and mirror images, and experimental, minimalist wall sculptures in aluminium. The 1970s saw a shift towards greater freedom of form. Abandoning the geometric visual language, he began experimenting with pretty much any material he could get his hands on.

In 1992, Carel Blotkamp wrote: "The sculptures of the last fifteen years pull together all the threads of his earlier work. Visser now freely makes use of the various sculptural principles he followed in successive periods in the past, and draws equally freely from the varied repertoire of form that he has built up over his long career."1

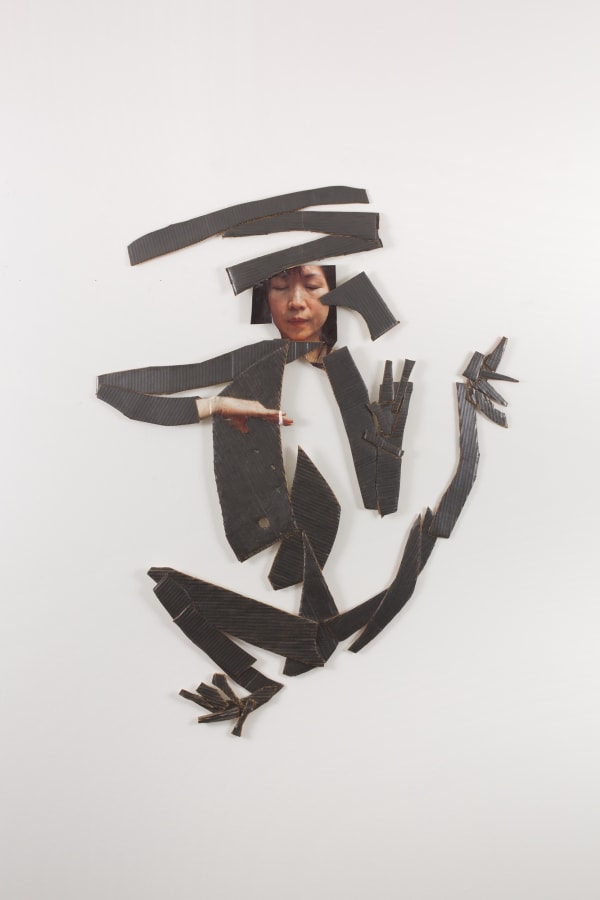

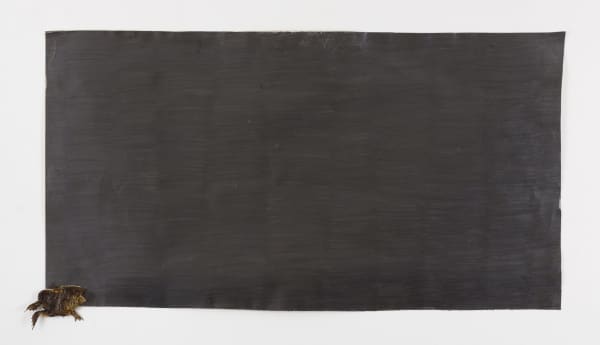

In 1999, Carel Visser moved with his wife to the south of France. Although Visser's love of iron as a sculpting material was undiminished, his 'ironclad' physical strength was slowly but surely deserting him. Undeterred, he continued working with the metal, but transitioned to lighter welded creations. In tandem, he applied himself to another, albeit related sculpting technique, cutting up cardboard to make what he dubbed 'wall sculptures'. He used graphite to give the cardboard a glossy sheen, then cut and processed it, sometimes with a collage of magazine illustrations, to be mounted on the wall as a two-dimensional sculpture. Though physically constrained, his artistic and creative capacity knew no bounds. In fact, Carel Visser was producing arguably the most unrestrained sculptures of his career.

1 Carel Blotkamp, De Verwondering, exh.cat. Apeldoorn (Van Reekum Museum), Lodz (Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi) 1992, p. 22